Transoxiana 12

Agosto 2007

Index

ISSN 1666-7050

|

Transoxiana 12 |

Each jewelry item represents a certain information symbol. Drawn from everyday

life, as well as from epos and myths, apothropaic emblems found in jewelry had

a magic power. The popularity of every particular subject was associated with

concepts of the epoch. The jeweller was involved in the events of his epoch;

ideas and concepts of the time were not foreign for him and were frequently

reflected in his art.

Each jewelry item represents a certain information symbol. Drawn from everyday

life, as well as from epos and myths, apothropaic emblems found in jewelry had

a magic power. The popularity of every particular subject was associated with

concepts of the epoch. The jeweller was involved in the events of his epoch;

ideas and concepts of the time were not foreign for him and were frequently

reflected in his art.

The images shown on the jewels enable us to track the architecture and sculpture, the utensils and clothes no longer in existence. Thanks to that, we can also have an idea of the hairstyles fashionable at that time. The function of the jewelry was not only meant to decorate the clothing; it was also connected to the life rites. They were primarily used for gala occasions- coronations, military rank awards, wedding and funerals. Jewelry had diverse social and ritual functions. So, apart from ornamentation, we can distinguish the following jewelry functions.(4):

When used as amulets, jewels had two main functions- those of protection and “propagation”, the latter implying fertility.

The images created by the ancients were thought to have magic power. Applying an image to an ornament or to a piece of clothing meant, “to animate them with spirit " It was a peculiar way to "sanctify" objects and associate them with the mystic powers of the other world.

All images were of a particular relevance, and were used by the ancients to influence the sun, the water, the earth, the animals,i.e. everything that was thought to be divine (16)

According to us, all art symbols are grouped around several binary oppositions (9). The binary opposition system underlay the art of the ancients and corresponded to the constructive principle of dualistic mythologies. Thus, the opposition between left and right was connected with differentiation of colors: the left symbolized femininity, and the right masculinity. The color of the former was red and the latter –white. The sun symbolized femininity and the moon symbolized masculinity .The unifotmity of religious outlook associated with the heavenly bodies gave an outlet to the similarity of material embodiment of these beliefs, irrespective of ethnic differences(5). Let us consider the images most frequently found among the archaeological remains of Central Asia, the emphasis being on the jewelry discovered in Bactria.These are golden and silver ornaments from the treasures of the Oxus (6), Tillya-tepe (3) and Dalverzin-tepe(7); they cluster around two deities: the Moon and the Sun.

A cross as an emblem of the Sun, which is a symbol of Resurrection and Immortality, is portrayed on the diadem discovered in the third tomb of Tillya-tepe. Like the circle and square, the cross-divided the inner and outer space emphasizing the concept of centrality. It provided the geometric representation of the World Tree symbolizing Death (21).Sometimes the cross was employed to represent lunar and solar radiation.

Constant interchangeability of the main deities, i.e. the Sun and the Moon, was also expressed by their symbolism. A sacred moon tree is one of the examples (1). The Sun and the Moon were perceived as kind and virtuous divine being punishing the vile and evil spirits. Their appearance meant life, health and well-being. These properties were transferred to the images of heavenly bodies, which were seen as magic protectors. (8)

Everything associated with God, heavens and non-existence was defined by odd numbers. In Central Asia, number seven was considered to be the most sacred number. Along with number three, the “magic seven” was the most popular number in different mythological systems. Its overwhelming magic power was attributed to its interconnection with the Moon phases and cycles (20). Special meaning and symbolism, holiness and perfection were attributed to it. Its indivisibility linked it, ipso facto, to God (1) and indicated the days of the week, Ursa Major the seven spheres, and seven colors. The numbers 3, 4,5,10,12,40,70 and 100 were sacred as well to many ancient peoples.

Odd numbers were related to happiness and well-being, and symbolized perfection. Number three is the most significant one in all mythological systems. It is an ideal model of any dynamic process implying creation, evolution and decay. This model is manifest in the vertical structure of the Universe (19) All the above symbols can be found in the ornaments of the period under study, both in shape and small details.

Number three was also believed to symbolize birth, life and death; the beginning, the middle and the end of everything; childhood, maturity and old age. It is central in classical mythology: Kerberos is three headed; there are three Fates, three Furies and three Graces; there are three Harpies and three Gorgons. It is also associated to the human being: Man has the body, the soul and the spirit. The same applies to solid matter, which has three dimensions. (1)

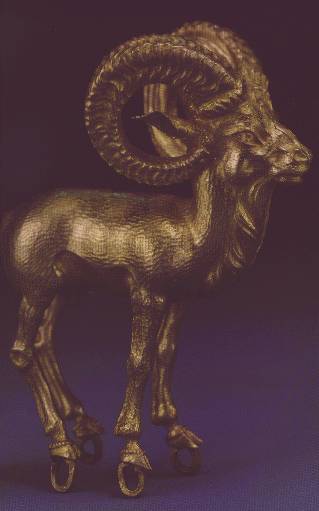

Zoomorphic images found in jewelry also had a symbolic meaning. Thus, the lion

was the symbol of supreme heavenly power and greatness, of the Sun and the Fire.

It was associated with intelligence, generosity, courage, fairness, pride, triumph,

arrogance, bravery and vigilance. The lion, as a symbol, was often depicted

on the coins of the ancient Graeco-Bactrian and Shaka kings, but it disappeared

in the Kushan period (17). The lion also symbolized the destructive power of

the female deity. In ancient Indo-European texts and folklore, wild animals

were considered to be sacred (2). In Central Asia, the mountain goat and the

ram were believed to be sacred bearers of solar energy. The Goat was worshipped

as a symbol of fertility. Its horns were represented on ornaments. The image

of the ram, as an embodiment of Pharn (good spirit, household protector), became

popular particularly in later periods, e.g. in Sassanian art.

Zoomorphic images found in jewelry also had a symbolic meaning. Thus, the lion

was the symbol of supreme heavenly power and greatness, of the Sun and the Fire.

It was associated with intelligence, generosity, courage, fairness, pride, triumph,

arrogance, bravery and vigilance. The lion, as a symbol, was often depicted

on the coins of the ancient Graeco-Bactrian and Shaka kings, but it disappeared

in the Kushan period (17). The lion also symbolized the destructive power of

the female deity. In ancient Indo-European texts and folklore, wild animals

were considered to be sacred (2). In Central Asia, the mountain goat and the

ram were believed to be sacred bearers of solar energy. The Goat was worshipped

as a symbol of fertility. Its horns were represented on ornaments. The image

of the ram, as an embodiment of Pharn (good spirit, household protector), became

popular particularly in later periods, e.g. in Sassanian art.

The bird was popular too, and is often found in the jewelry production embracing a period of eight centuries (4th century B.C. - 4th century A.D.). In Iranian mythology, it was identified with Supreme Wisdom, with Fire and Sun. In Indo-Iranian mythology the bird, particularly the water fowl, personified and accompanied the Mother-Goddess and was associated with the Water. In rituals, the image of pair of birds was symbol of fertility, wealth and well-being. In the folklore of many peoples, pair of ducks was a symbol of marital love (13)

Fertility was also associated with the image of snake. An earring from Dalverzin-tepe shaped, as a snake is one of the multiple examples of this image widely used in jewelry. Almost all mythologies connect the snake to the earth female fertility power, the water and the rain.

The use of a snake’s head in jewelry emphasizes the concept of the snake as a defender. Stylized snake motifs are frequently found in bracelets. These were obviously designed to protect against the evil spirits and evil eye. Snakes were believed to protect the souls of the dead from the evil spirit. The Tajiks inhabiting mountain regions believed in the existence of the great wizard Shokhi Moro (The King of Snakes) who dwelt on a mountain peak and ruled over all the snakes and dragons.

The snake motifs were used in the ornaments of the Pamir settlements -in those of Darvaz, Vanch, Yazgulem, Rushan and Shugnan, which proofs that the same mythological symbols circulated in different areas (12). The Greeks worshipped the snake Erichthonios, son of the Goddess of the Earth, and snakes were kept in great number in the temple of Athena as a tribute to the Goddess of Wisdom.

In India, Vishnu, one of the gods of the triad, was depicted lying on the great

snake Sesha (18). The lunar snake, much like horns and thorns, was among the

most widely spread symbols of the Moon religion. The snake and the fish were

interchangeable symbols.

In India, Vishnu, one of the gods of the triad, was depicted lying on the great

snake Sesha (18). The lunar snake, much like horns and thorns, was among the

most widely spread symbols of the Moon religion. The snake and the fish were

interchangeable symbols.

Among the imaginary animals represented in jewelry, the most popular one is the gryphon (animal-shaped bracelets nos.116 and 116a from the treasure of Oxus) (6). In Central Asia, the gryphon first appeared in the 5th-4th centuries B.C. Its original iconography was formed in the early states of the Front-Asian world. In Greek mythology, the gryphon is a monstrous bird with the beak of an eagle and the body of a lion.

In the ancient and medieval art of Central Asia, the gryphon was a protector from evil, witchcraft and secret slander. The image of the lion-gryphon penetrated into Central Asian art in 5th-4th century B.C. from Achaemenian Iran. The Greeks, however, believed that it originated from Bactria and that each historical-artistic area produced its own version of a gryphon: a lion-gryphon, a dog-like gryphon, a horse-like gryphon, etc. (15)

The plastic interpretation of the gryphon becomes more generalized in the monumental art of Tokharistan, which is to some extent connected to its architectural role. In early Sogdian art, the rendering of this image becomes monumental and decorative (13)

Sphinxes, in Egyptian jewelry, represented the floods of the Nile occurring in the periods of solstice in the constellations of Leo and Virgo (14). That is why the sphinx was represented as a lion with a male or female head. The sphinx was considered the emblem of wisdom and power. In Greek mythology, it was a monster begot by Typhon and Echidna with female face and breasts, a body of a lion and wings of a bird. (15)

Among the anthropomorphic images are those of the gods. In the period from

4th century B.C. to the 2nd century AD the pantheon in Bactria expanded from

Hermes and Zeus to the Dioskoroi, Heracles, Apollo, Athena, Artemis, Nike, Dionysus,

Poseidon, Tyche, Demeter,Aphrodites. To these gods Kybele from the Middle East

and Nana were added. The appearance of Cupids, Aphrodite’s’ sons and companions

is only natural. In terms of cosmogony, Orphics treated Cupid, i.e. Eros, as

an embodiment of the law ruling Universe. In Chaos, he symbolized the creator

of cosmos and the original power of conception, which was one of the elements

of the world creation. Eros, like other demoniac creatures, was given wings

to emphasize his demonic nature. Till the Hellenistic epoch, painters and sculptors

constantly portrayed Eros with huge wings. Due to the fact that Greek and Hellenistic

works of art were widely exported to the oriental countries as far as India,

in the East the iconography of Eros became well known in the early historical

period. The representation of Cupids and Aphrodite in female jewelry emphasized

sensuality.

Among the anthropomorphic images are those of the gods. In the period from

4th century B.C. to the 2nd century AD the pantheon in Bactria expanded from

Hermes and Zeus to the Dioskoroi, Heracles, Apollo, Athena, Artemis, Nike, Dionysus,

Poseidon, Tyche, Demeter,Aphrodites. To these gods Kybele from the Middle East

and Nana were added. The appearance of Cupids, Aphrodite’s’ sons and companions

is only natural. In terms of cosmogony, Orphics treated Cupid, i.e. Eros, as

an embodiment of the law ruling Universe. In Chaos, he symbolized the creator

of cosmos and the original power of conception, which was one of the elements

of the world creation. Eros, like other demoniac creatures, was given wings

to emphasize his demonic nature. Till the Hellenistic epoch, painters and sculptors

constantly portrayed Eros with huge wings. Due to the fact that Greek and Hellenistic

works of art were widely exported to the oriental countries as far as India,

in the East the iconography of Eros became well known in the early historical

period. The representation of Cupids and Aphrodite in female jewelry emphasized

sensuality.

In different epochs jewellers treated the same myths and images differently,

and their works of art reflected a variety of attitudes and concepts characteristic

of each epoch. Thus, in one case the god Bes in the jewelry items from the Amu-Darya

treasure was depicted as a symbol of the king’s power and courage (13). This

image may have been transformed into the image of Sylenos as, for instance,

on the clasp found in the treasure of Tillya-tepe representing a “wedding scene”

(3)

In different epochs jewellers treated the same myths and images differently,

and their works of art reflected a variety of attitudes and concepts characteristic

of each epoch. Thus, in one case the god Bes in the jewelry items from the Amu-Darya

treasure was depicted as a symbol of the king’s power and courage (13). This

image may have been transformed into the image of Sylenos as, for instance,

on the clasp found in the treasure of Tillya-tepe representing a “wedding scene”

(3)

Among floral decorations, the lotus is one of the most frequently represented images (13). Lotus embodies creative power of the female nature and symbolized fertility, posterity, longevity, health and vitality. In later periods in apparently transforms into a tulip, often found in the embroidery of Central Asia.

A tree with birds on its branches symbolized fertility, happiness and prosperity. One of the Avesta hymns glorifies the sacred tree possessing the seeds of all the plants existing on the Earth. Some of the birds are plucking the branches; others are picking up the fallen seeds and carrying them to the sky, from where they return to the Earth with the rain to give birth to new plants. In the period going from 5th century B.C. to the 5th century A.D., the headdresses of the Eurasian steppe nobility were traditionally adorned with the image of the tree with birds on its branches. (11) The decorative style of the robe and the crown of a Bactrian woman implied that the bearer of those items was not only a noble, but belonged to the ruling clan, that she was a queen and represented the Goddesses of Fertility. All her regalia were symbolized by the Tree of Life on the crown. The above-mentioned objects were found in the sixth tomb of Tillya-tepe. The motif of the Tree of Life surrounded with animals was particularly popular in the first millennium B.C. In this period Iranian – speaking tribes were settling down, and the evolving pictorial art of the Scythes was influenced by North-Iranian art.

The image of the tree with birds on its branches was placed, in particular,

on the ceremonial headdresses of Scythian kings and queens and was associated

with the Goddess of Fertility expressing the idea of life revival. Mythologists

have proved that the image of the tree reflects the principal cosmogonic myth:

the universe was represented by its three sections – the roots, the trunk and

the crown. The roots symbolized the underworld; the trunk was associated with

the surface of the earth and the world of humans and animals, while the crown

referred to the heavens, the domain of the gods. Sometimes the four parts of

the world were marked by four trees growing on the four sides of the World Tree

(10)

The image of the tree with birds on its branches was placed, in particular,

on the ceremonial headdresses of Scythian kings and queens and was associated

with the Goddess of Fertility expressing the idea of life revival. Mythologists

have proved that the image of the tree reflects the principal cosmogonic myth:

the universe was represented by its three sections – the roots, the trunk and

the crown. The roots symbolized the underworld; the trunk was associated with

the surface of the earth and the world of humans and animals, while the crown

referred to the heavens, the domain of the gods. Sometimes the four parts of

the world were marked by four trees growing on the four sides of the World Tree

(10)

In Chinese philosophy, which influenced Central Asian beliefs, the tree is one of the five elements of life: the tree, the fire, the earth, the metal and the water. They evolved from chaos in the process of interaction between two poles, Yin and Yang. These are the essential categories of natural philosophy signifying the unity of polar forces, the forces of the soft and the hard, the female and the male, the light and the dark, etc.(10) In Korean mythology the image of the tree, for instance, embodied the magic contract between Man and the other world.

Symbolic properties were attributed not only to metals (the Sun was associated with gold and the Moon with silver) but also to the precious stones used in jewelry. In the history of culture, stones had particular significance as durable substances resisting destruction. The worship of stones was connected with the belief in their healing properties. Stones were endowed with magic healing power, which evoked when they were touched or worn as amulets or ground and swallowed as a medication. To reinforce the magic powers of the semiprecious stones, jewelers increased their dimensions on the ornaments and multiplied their number.

Among the stones popular with the jewellers of the period under study were turquoise, garnet, lapis lazuli, pearls, cornelian and coral. Turquoise symbolized purity and virginity, it indicated dignity and wealth. It was supposed to safeguard travelers on their way and reconcile spouses; it was believed to improve eyesight and to help in communication (1).

The notion of magic powers of the stones intermingles with the rational approach to their utilization in folk medicine. The peoples of Central Asia used pearls and corals to treat lung diseases. When powdered, they were used to stop bleeding and as astringents. Corals were considered to bring prosperity and fertility (2). This special attachment to corals and pearls may stem from astral cults.

Pearl application in earring and necklaces evoked the sparkle of the Moon and were allegedly bringing wealth to those wearing the ornaments.

Carnelian was associated with Mercury and Venus, the planets named after patrons

of trade: the God of Wisdom and the Goddess of Beauty and Fertility. There are

two different types of carnelian, which are distinguished as male and female

stones. Male carnelian is of a crude brown color, while female is pinkish orange

transparent. This stone was believed to protect eyesight, safeguard home and

bring happiness and prosperity.

Carnelian was associated with Mercury and Venus, the planets named after patrons

of trade: the God of Wisdom and the Goddess of Beauty and Fertility. There are

two different types of carnelian, which are distinguished as male and female

stones. Male carnelian is of a crude brown color, while female is pinkish orange

transparent. This stone was believed to protect eyesight, safeguard home and

bring happiness and prosperity.

The shape of each jewel and ideas underlying it reveal the two basic reasons for wearing it - reason that, in their turn, determine the meaning codified in a particular item. The first reason, aesthetical, is based on the intention to emphasize female beauty in accordance with local ideals and to stress the male power and masculinity. The second reason, ritual, reflects ideological concepts handed down by the previous generations expressed in the belief in the protective powers of the ornaments used as talismans. When performing religious rites, fine arts were essential in order to record the secret meaning of the ceremony in visual form. Characters depicted in jewelry, as well as their attributes and gestures, did not have any actual narrative meaning. Rather, they were signs to be deciphered and translated into the language of concepts.

© The Author(s) -- Los artículos son propiedad de sus autores. (Ley 11.723)

© The Author(s) -- Los artículos son propiedad de sus autores. (Ley 11.723)